“The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.”

— John Muir

Decoding Plant Extracts

What “Standardised Extracts” and “Extract Ratios” Actually Mean

Walk into the world of supplements and you’ll see a lot of numbers.

10:1. 50:1. 2% this. 12% that.

It looks scientific. But does it actually tell you anything useful?

Let’s slow this down and make sense of it — without the jargon, without the marketing fluff, and without pretending every extract is created equal.

First things first: what is a plant extract?

At its simplest, a plant extract is just this:

You take a plant.

You add a solvent — usually water, alcohol, or a combination of both.

That solvent binds to specific compounds in the plant.

The solvent is then removed, leaving behind a concentrated extract.

That’s the whole process in plain English. No magic. No mystery. Just chemistry doing its job.

Extract ratios: what do those numbers really mean?

An extract ratio is usually written like this: X : Y

In plain English:

X = how much raw plant material you start with

Y = how much extract you end up with

That’s it. No guarantees. Just a ratio.

Common extract ratios (decoded)

1:1 extract

One part plant → one part extract. Very close to the original plant material. Often used when a broad, whole-plant profile is desired.

4:1 extract

Four parts plant → one part extract. More concentrated. Lets you use less material for the same amount.

10:1 extract

Ten parts plant → one part extract. Highly concentrated. Commonly used where space or capsule size matters.

Here’s the catch: an extract ratio tells you nothing about what’s actually in the extract.

It doesn’t tell you which compounds survived extraction, whether the active compounds are present, or whether two batches are remotely similar.

Standardised extracts: consistency over guesswork

A standardised extract focuses on what the extract contains — one or more identified compounds, present at a guaranteed minimum level, tested batch to batch.

Why standardisation matters

- Consistency — the extract behaves the same every time

- Reliability — what’s on the label is actually in the product

- Quality control — batches can be compared and validated

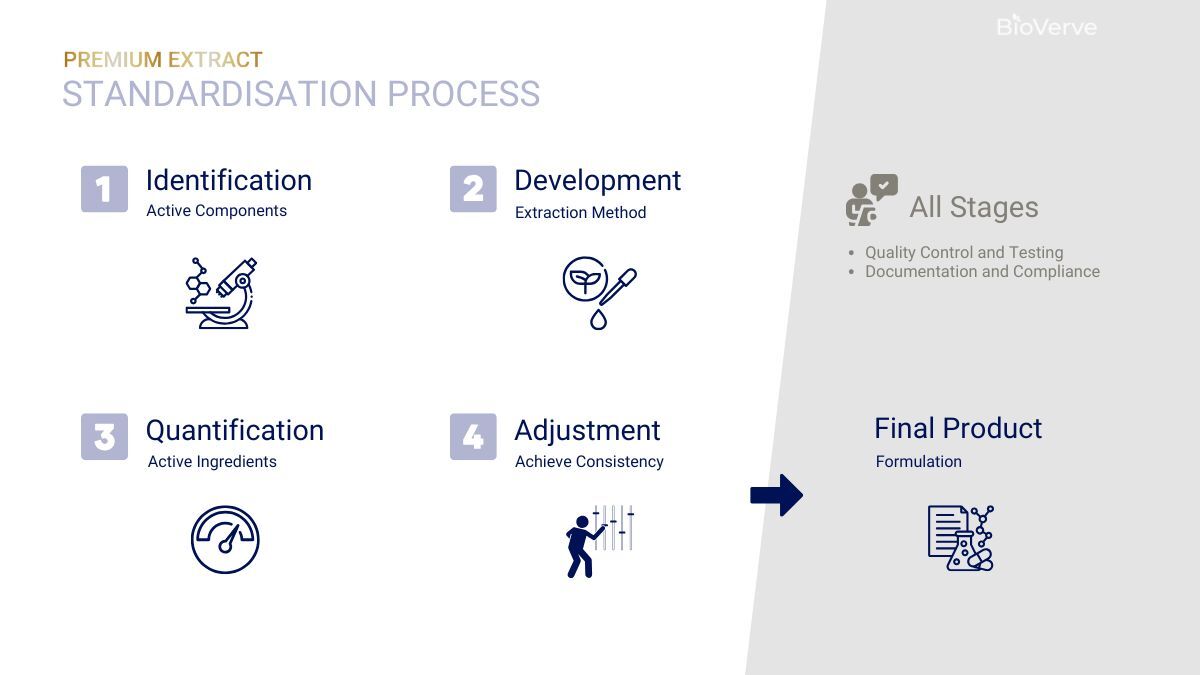

How standardised extracts are made (without the lab-speak)

- Identify the key compounds linked to traditional use or research

- Extract using methods designed to preserve those compounds

- Measure the actives using analytical methods

- Adjust (e.g., blend/refine) so each batch meets the target level

- Test and document for quality, purity, and consistency

A couple of real-world examples

Tongkat Ali & eurycomanone

BioVerve’s Malaysian Tongkat Ali is standardised to 2% eurycomanone. That matters because standardisation helps keep the product consistent from batch to batch.

Fadogia agrestis: when standardisation isn’t possible

Fadogia agrestis is a good example of why extract ratios still exist. At the moment, there isn’t enough research to justify standardising to a single “key” active compound.

Instead, BioVerve offers Fadogia as a finely milled powder and as a 10:1 extract, and tests for rutin as an indirect marker for batch-to-batch consistency.

Can extracts be independently tested?

Standardised extracts: yes

Third-party labs can validate standardised extracts by measuring the active compounds using reference standards.

Extract ratios: not really

Extract ratios can’t be reliably verified from the extract alone — a lab would typically need the original raw material and manufacturing context to even estimate the ratio.

So… what does this actually mean for you?

- If research has identified key compounds, a standardised extract is usually the better choice.

- If research is limited, extract ratios can still be useful — but transparency matters.

- Very large ratios (e.g., 50:1, 100:1) should prompt questions, not assumptions.

- Numbers don’t equal quality. Clarity does.

Further reading

- IntechOpen: Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants and Herbs

https://www.intechopen.com - MDPI: Phytochemicals: Extraction, Isolation, and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Extracts

https://www.mdpi.com

Questions? You can reach me at mo@bioverve.co.uk.